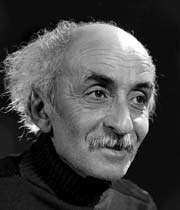

Nima Yushij (The Father of Modern Persian Poetry)

Nima Yushij (نيما يوشيج in Persian) (November 12, 1896 - January 6, 1960) also called Nima, born Ali Esfandiari (Persian: علي اسفندياري), was a contemporary Tabarian and Persian poet who started the she’r-e no ("new poetry") also known as she’r-e nimaa"i ("Nimaic poetry") trend in Iran. He is considered as the father of modern Persian poetry.

He was the eldest son of Ibrahim Nuri of Yush (a village in Nur County, Mazandaran province of Iran). He was a Tabarian but had also Georgian roots. He grew up in Yush, mostly helping his father with the farm and taking care of the cattle. As a boy, he visited many local summer and winter camps and mingled with shepherds and itinerary workers. Life around the campfire, especially images emerging from the shepherds' simple and entertaining stories about village and tribal conflicts, impressed him greatly. These images, etched in the young poet's memory waited until his power of diction developed sufficiently to release them.

Nima's early education took place in a maktab. A truant student, the teacher had to seek him out in the streets, drag him to school, and punish him. At the age of twelve, Nima was taken to Tehran and registered at the St. Louis School. The atmosphere at the Roman Catholic school did not change Nima's ways, but the instructions of a thoughtful teacher did. Nezam Vafa, a major poet himself, took the budding poet under his wing and nurtured his poetic talent.

From his father, a boastful man, skilled in horse riding, hunting and playing the tar (Persian lute), Nima Yushij inherited a naive but strong sense of pride which could be interpreted as arrogance. His mother, mild in nature, born and bred in a family of good education and learning, knew by heart many classical stories, such as Nezami"s "Haft Peykar" (The Seven Beauties), and many poems, specially Hafez"s ghazals, which she related and recited to him. This was how Nima became so fascinated with Nezami and Hafez and remained an ardent admirer of their work, all his life.

Instruction at the Catholic school was in direct contrast to instruction at the maktab. Similarly, living among the urban people was at variance with life among the tribal and rural peoples of the north. In addition, both these lifestyles differed greatly from the description of the lifestyle about which he read in his books or listened to in class. Although it did not change his attachment to tradition, the difference set fire to young Nima's imagination. In other words, even though Nima continued to write poetry in the tradition of Saadi and Hafez for quite some time his expression was being affected gradually and steadily. Until, eventually, a time came when the impact of the new became too overwhelming. It overpowered the tenacity of tradition and led Nima down a new path. Consequently, Nima began to replace the familiar devices that he felt were impeding the free flow of ideas with innovative, even though less familiar devices that enhanced a free flow of concepts. "Ay Shab" (O Night) and "Afsaneh" (Myth) belong to this transitional period in the poet"s life (1922(.

In the long years of experimenting with different forms of classical poetry, he tried to imitate Nezami by writing a dramatic long poem, about 1500 couplets, and the result is "Ghal"e-ye Seghrim" (Seghrim Fortress), displaying all the shortcoming of a novice in composition and versification....

With my poetry I have driven the people into a great conflict;

Good and bad, they have fallen in confusion;

I myself am sitting in a corner, watching them:

I have flooded the nest of ants.

In general, Nima manipulated rhythm and rhyme and allowed the length of the line to be determined by the depth of the thought being expressed rather than by the conventional Persian meters that had dictated the length of a bayt (verse) since the early days of Persian poetry. Furthermore, he emphasized current issues, especially nuances of oppression and suffering, at the expense of the beloved's moon face or the ever-growing conflict between the lovers, the beloved, and the rival. In other words, Nima realized that while some readers were enthused by the charms of the lover and the coquettish ways of the beloved, the majority preferred heroes with whom they could identify. Furthermore, Nima enhanced his images with personifications that were very different from the "frozen" imagery of the moon, the rose garden, and the tavern. His unconventional poetic diction took poetry out of the rituals of the court and placed it squarely among the masses. The natural speech of the masses necessarily added local color and flavor to his compositions. Lastly, and by far Nima"s most dramatic element was the application of symbolism. His use of symbols was different from the masters in that he based the structural integrity of his creations on the steady development of the symbols incorporated. In this sense, Nima's poetry could be read as a dialog among two or three symbolic references building up into a cohesive semantic unit. In the past only Hafiz had attempted such creations in his Sufic ghazals. The basic device he employed, however, was thematic, rather than symbolic unity. Symbolism, although the avenue to the resolution of the most enigmatic of his ghazals, plays a secondary role in the structural makeup of the composition.

Nima died of pneumonia in Shemiran, in the northern part of Tehran and was buried in his native village of Yush, Nur County, Mazandaran, as he had willed.

Sources:

wikipedia.org

art-arena.com

Other Links:

Kamal-ol-Molks Style

Kamal-ol-Molk’s experience abroad

Ferdowsi , A gifted persian poet

Parviz Tanavoli, (an Iranian sculptor, painter, art historian and collector)

Shahryar, an emotional poet

Mehdi Akhavan Sales

Sohrab Sepehri